Press room

"The Moscow Times", September 22, 2006.

Escape Artist

He longed for freedom in the Soviet era, then left for the West in the 1990s. Now, painter Erik Bulatov comes home with a major retrospective.

By Alastair Gee

Published: September 22, 2006

All his younger life, Erik Bulatov dreamed of escape. He fantasized about a breathless freedom from communism, and from the restraints of the material world itself: He wanted to soar on ideas through a yawning azure sky.

All his younger life, Erik Bulatov dreamed of escape. He fantasized about a breathless freedom from communism, and from the restraints of the material world itself: He wanted to soar on ideas through a yawning azure sky.

But in Bulatov's dissident paintings from the restrictive Khrushchev and Brezhnev years, which went on display this week in the artist's first major show in Russia, he shows every hope checkmated and any lift toward the heavens halted. The brutal Soviet slogans he borrows - "Glory to the Communist Party" and the "Do Not Lean" sign from metro cars - obscure his pictures' horizons and weigh on the viewer with suffocating force.

Bulatov, 73, is lauded in the West but little known at home, partly because he has lived in Paris since the Soviet collapse. But the New Tretyakov Gallery seems determined to change that. "Erik Bulatov: That's It," his retrospective that opened Tuesday, is housed in a hall that the museum typically reserves for the most prominent artists. Dozens of collectors and galleries from Europe and the United States donated his best-known pieces for the show, and lavish catalogs are on sale in Russian and English.

The artist has come a long way since the Soviet era, when it was impossible for him to hold public exhibitions due to pressure from the authorities. All he could do was invite friends into his studio, located near what is now the Chistiye Prudy metro station, where he painted on the side when he wasn't illustrating children's books.

These days, Bulatov says he wants to spend more time working in Moscow. But whether that happens depends, in part, on the way his show is received: He is worried that communism corrupted the way people perceive, and that they will not understand his pictures.

"I have a picture where it's written: 'I live, I see.' This is my credo," Bulatov said in an interview last week. "My business was [to depict] the modern consciousness, comprised of the normal things that appear every day, to which people don't even pay attention."

"I have a picture where it's written: 'I live, I see.' This is my credo," Bulatov said in an interview last week. "My business was [to depict] the modern consciousness, comprised of the normal things that appear every day, to which people don't even pay attention."

His works take a playful approach to art history, bringing together flashes of Russia's avant-garde with its 19th-century realist tradition. Shimmering behind the text elements, reminiscent of Mayakovsky's 1920s posters advertising beer and rubber, are moving landscapes and portraits drawn as precisely as a draftsman might.

The Bulatovs have been helping set up the show for weeks. During a recent visit to the museum, he signed his name on the wall in paint and ambled around in overalls to greet visitors, and his wife, Natasha, a ballet critic, watched curators give tours and pointed out highlights she thought they were missing. Russian and foreign television crews stopped by to interview the artist.

"That's It" is arranged chronologically, and ends in an annex where Bulatov's Soviet-era book illustrations are displayed. The sensation of walking through the main section is one of being increasingly choked of air.

The tension that grips his later pictures is hinted at in early works from the 1960s, where trembling, fleshy forms are riven apart or explode. Bulatov seems frustrated with the possibilities open to him, artistically as well as personally, and in one self-portrait he gazes from a world of rigid shapes and blocky colors at a painting of an alluringly indistinct lakeside.

Feelings of alienation climax in "Horizon," one of the first works in a style that is recognizably his. He has painted a beach panorama with a group of people walking toward the seashore. But stamped across the horizon, obscuring the vanishing point where the sky and ocean should meet, is a plain red-and-gold banner. Resembling a ribbon tied around the picture, it is entirely foreign to the landscape it obliterates.

Feelings of alienation climax in "Horizon," one of the first works in a style that is recognizably his. He has painted a beach panorama with a group of people walking toward the seashore. But stamped across the horizon, obscuring the vanishing point where the sky and ocean should meet, is a plain red-and-gold banner. Resembling a ribbon tied around the picture, it is entirely foreign to the landscape it obliterates.

As the strip -- perhaps a Communist Party banner to be hung from streetlights -- simultaneously draws and repels the viewer's gaze, another inconsistency jumps out: People in bathing costumes paddle in the ocean, yet a woman in the foreground wears a long winter coat, and the men are in black suits, as if all are oblivious to their summer seaside surroundings, or have been beamed down from somewhere else.

These jarring elements shock the viewer into suspicion of the picture-postcard beach scene, an idealized Soviet Union as seen in propaganda posters. And the figures exemplify Bulatov's idea of a citizenry desensitized to their manipulated social space. "People lived in this deformed space their whole lives, and they'd already begun to conceive it as normal," he said. "I tried to show with my pictures that this normality was abnormal."

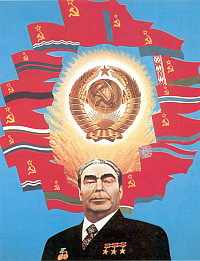

Bulatov is rarely ironic in his deployment of Soviet symbols; his reproductions of Brezhnev paintings, for example, are faithful. Instead, he undermines them, showing the normal to be abnormal, by introducing glitches in space and perspective. Brezhnev in the Crimea portrait seems to be floating in air, with no connection to the picture's misty background. "Soviet Cosmos" is hung so the leader's face is at waist-level, yet, unsettlingly, he still seems to be standing above the viewer.

Grounding his other motivations is Bulatov's yearning to escape, not only from the restraints of communism but also, perhaps, from the bindings of the real. In pictures that insist "Go" and then contradict it by overlaying the order "Stop," or that invite with "Entrance" and renege with "No Entrance," Bulatov wants nothing more than to accede to the positive commands and disappear into the distance. That desire becomes wistful and poignant in "Melting Clouds," a view from below of trees ringing a languorous sky.

Sometimes, for a few moments, he attained the release he wanted. "When I did my painting 'I'm Going,'" he recalled, "I had the feeling suddenly not that I was drawing clouds, but that with my hands I was making actual clouds. It was an unbelievable feeling of happiness."

It did not last, though. Bulatov continued to feel paralyzed amid the stagnation of the Brezhnev era, unable to move in a system that said people had freedom while denying it to them at the very same time.

It did not last, though. Bulatov continued to feel paralyzed amid the stagnation of the Brezhnev era, unable to move in a system that said people had freedom while denying it to them at the very same time.

Today, these paintings face the accusation of being irrelevant, or of saying nothing that Russians haven't seen from other dissident artists. Bulatov argues they could alert people to the ideology of the capitalist marketplace. As for the works where structures and people are painted over to become red silhouettes, he suggests that those who grew up under communism still see through the worldview it imparted to them.

Unlike many other former dissident artists, Bulatov has found financial security, with his paintings fetching high prices in the West. He and his wife keep an apartment in Paris' prestigious second arrondissement, a short walk from the Louvre and the Centre Pompidou.

Bulatov's paintings since the Soviet collapse have a softer feel to them, seeming to have lost the urgency that communism lent his earlier work. The need to escape has become less compulsive.

In "Window," from 1998, a gauzy white sheet is fastened across an open pane. Hidden behind it runs the quiet, tree-lined Parisian street that hugs the Bulatovs' apartment; glowing sunlight teases the edge of the hanging, flaring near its center.

Only three small pins hold the fabric in place, and a triangular chink of sky beckons. But Bulatov is content to wait, floating in space, poised. Here, perhaps, he paints a beyond that will eventually, undoubtedly, steal over and embrace him forever.

"Erik Bulatov: That's It" (Erik Bulatov: Vot) runs to Nov. 19 at the New Tretyakov Gallery, located at 10 Krymsky Val. Metro Oktyabrskaya, Park Kultury. Tel. 230-7788, 951-1362, 238-1378.